This is the story of the rooster sacrifice that shaped the course of Michigan football history.

Stick with me.

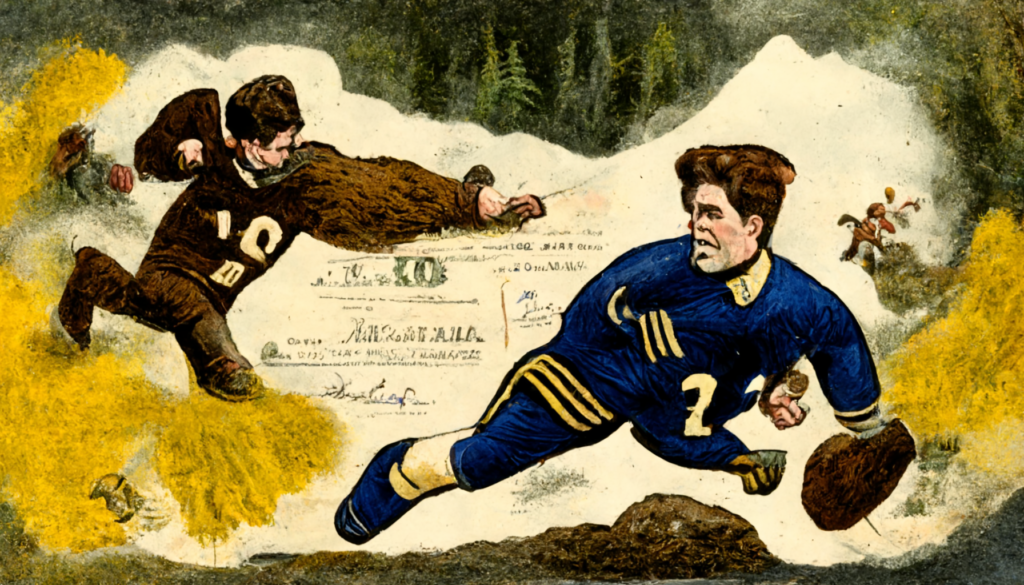

Before Ohio State, the University of Chicago was Michigan’s primary rival. The two programs first faced off during UC’s debut season of 1892. The Wolverines and Maroons played annually on Thanksgiving Day, the last week of the season. Michigan’s 12-11 victory to finish an undefeated 1898 season inspired a music student named Louis Elbel to write “The Victors,” later adopted as the fight song, on his return journey from Chicago to Ann Arbor.

After a one-year hiatus, Michigan and Chicago resumed their rivalry on Thanksgiving Day, 1900, in the Windy City.

A CONTRAST IN COACHES/A YUKON DETOUR

In this nascent age of college football, the vocation of coaching was just beginning to be professionalized. Chicago was an outlier, helmed since 1892 by Amos Alonzo Stagg, who’d already transformed the game by the turn of the century with innovations such as the huddle, the lateral and the tackling dummy.

Michigan had a more typical coaching history for the time. It introduced its first head coach in 1891, then went through five more in the ensuing ten years. Only one head man, Gustave “Dutch” Ferbert, lasted more than two seasons. Ferbert coached the Wolverines to a 24-3-1 record from 1897-99, claiming the program’s first conference title in ‘98.

Needless to say, salaries back then didn’t compare to today’s eight- and nine-figure deals. Ferbert saw an opportunity to go west – not, say, to coach USC or Stanford, but to mine for gold in Alaska.

After years of little word from the expedition – to the point that our intrepid hero was presumed dead at multiple points – the Detroit Free Press reported in 1909 that Ferbert “became a bonanza king overnight”:

Gustave H. Ferbert, known to football followers the country over as “Dutch,” has made a “million-dollar touchdown.” …

Quitting the gridiron game “Dutch” hiked for Nome, Alaska, in 1900 to make his fortune. He has returned rich. He made a “killing” somewhere near Deering City in the Candle Creek region this and last year and if he cares to go back his claims are valuable enough to put him in the millionaire class.

“‘DUTCH’ FERBERT IN LUCK,” Detroit Free Press, 22 Oct. 1909, archived.

Reports on Ferbert’s riches may have been exaggerated. The rest of his life was not well-documented. When he died in 1943, obituaries mentioned that he spent his post-Alaska years working as a mining engineer, not enjoying a Scrooge McDuck lifestyle.

While Ferbert made his Yukon trek, Michigan looked for a new coach. Athletic director Charles Baird chose Langdon “Biff” Lea, the third former Princeton player to coach the Wolverines, after a faith-testing search went into July. Lea, who had been the unofficial coach of the Princeton side the previous year, was supposed to be worth the wait, according to the Free Press:

There has been considerable complaint among the students on account of the delay in arranging for next year’s football work, but no one suspected the magnitude of the star Director Baird was trying to secure.

“Michigan Eleven to Have Princeton’s Old Coach,” Detroit Free Press, 13 Jul. 1900, archived.

Upon arrival, Lea “established a set of strict rules for his team,” according to the Bentley Library:

Posted on the wall of the Gymnasium before tryouts, the stipulations included: “The word ‘Can’t’ is not in the football vocabulary. Any man feeling that way about any part of the game in detail is not wanted on the field and will please stay away. Only those wanted who say ‘I will’ with teeth together and who never stop fighting. Otherwise, they go off the field.

The clichéd fresh-faced football coach instilling a tougher culture to distinguish himself from his predecessor has been around a long time. There’s no word on whether Lea installed a more aggressive, multiple defensive scheme.

Lea’s debut season indicated his focus may have been too much on rule-establishing and not enough on ball-knowing. The Wolverines surpassed 12 points only once during a rickety 6-0 start, got embarrassed 28-5 by Iowa, eked past Notre Dame, then played Ohio State to a scoreless tie five days prior to the Chicago game. The Buckeyes, still independent at the time, had lost the previous week to Ohio Medical University.

The Maroons were the reigning Western Conference champions after a breakthrough 12-0-2 (4-0 WC) season in 1899. They’d fallen on even harder times than Michigan, however, losing a program-record five consecutive games, most recently a 39-5 drubbing at the hands of Wisconsin. While Chicago had the benefit of a week more rest than its rivals, it entered Thanksgiving as the underdog.

“The Absence of the Championship Feature Detracts Little From the Annual Michigan–Chicago Game,” declared a Michigan Daily headline.

Despite the slump, Stagg had unlimited job security – he was, after all, the most innovative coach in the history of the game. The same couldn’t be said for Lea. The Daily wrote in the leadup, “[Chicago] now makes the single boast that, bad as she is, she can still win from Michigan.”

Lea’s front-page quote made the gravity of his situation clear.

“We have got to win, so we will win.”

MICHIGAN STRIKES FIRST

According to the Chicago Tribune, 3,000 Michigan fans made the trip to Chicago’s Marshall Field, where 4,000 Maroons partisans occupied the other side. With a listed attendance of 10,000, the game attracted considerable casual interest, too.

At 2 p.m., the Wolverines sent the opening kickoff from the 55-yard line – the field stretched 110 yards from goal line to goal line. Chicago’s offense converted three first downs to move near midfield as “the maroon rooters went wild.” They quieted when left halfback James M. Sheldon lost a fumble to Michigan.

The Wolverines methodically bashed their way towards the goal line, covering 47 yards in 20 plays for the game’s opening score; 5’10½, 175-pound left tackle Hugh White tallied five points with a one-yard touchdown plunge and fullback Everett Sweeley kicked the one-point goal through the uprights.

The ensuing kickoff featured a rugby-style rules quirk: Chicago kicked off from midfield. Sweeley fielded the ball inside the 15-yard line, retreated a few steps, and punted the ball back to the Maroons, who returned the ball inside the U-M 50. They gained only five yards before losing the ball on downs.

Michigan’s opportunity to move ahead by two possessions instantly slipped through its fingers. Sweeley dropped “a poor pass” (a lateral, your author presumes) on first down, and rather than eat a tackle for loss, he quick-kicked the ball out of bounds near the UC 50.

About that.

THE ORIGINAL PUNT GOD

Sweeley deserves an aside. He had never seen a football game before playing in one as a collegian but still managed to earn the rare distinction of freshman varsity letterman. A sophomore in 1900, he’d play two more seasons for Michigan and set some astonishing records as a dual-threat runner/kicker [emphasis mine]:

Ev Sweeley, of Michigan, holds the two most prized records for kicking a football. In a game with Iowa in [1902], Sweeley administered to the prolate the longest kick on record. A ball from his right foot went 86 yards before touching the ground. Sweeley also boasts an enviable distinction unboasted by any other hero of the gridiron. Never in the four years of his playing days did the Wolverine have a single punt blocked. …

Sweeley was also an expert place kicker, scoring over 100 points in this manner. His greatest game was the running punt trick. He would run a ball until he was hard pressed and then kick, often thus adding many yards to the ground gained.

“SPECTACULAR FIGURE IN FOOTBALL IS THE BOOTER,” Buffalo Courier, 11 Nov. 1906, archived.

Sweeney starred in the inaugural Rose Bowl, held on New Year’s Day of 1902. In Michigan’s 49-0 victory over Stanford, a trouncing that caused the second Rose Bowl to be put off until 1916, he made four field goals and averaged 38.9 yards on 21(!) punts.

He was ever-present in the lineup with one noteworthy exception:

In four seasons he missed only one game, the result of “a little row with a math professor.”

“Kicked Four Years Without a Block,” Harrisburg Telegraph, 03 Nov. 1943, archived.

Sadly, no additional details were provided. Sweeley went on to a brief, three-sport coaching career at Washington Agricultural (now Washington State) before moving to Twin Falls, Idaho, where he became a lawyer. He remained in that field, working as the county prosecutor and a probate judge later in life.

CHICAGO STRIKES BACK

While prudent, Sweeley’s running punt didn’t have the desired impact. Stagg had made a number of lineup changes heading into the game, as “injuries, idleness, and faculty’s blue pencil” had necessitated an overhaul. One varsity newcomer, in particular, began to infuse life in the Maroons: fullback Ernest E. Perkins, who’d previously played on the “scrub team.”

As the Daily put it, with a dash of salt:

The game showed up for the Midway team some stars heretofore unheard of. Men who had previously not enjoyed the dignity of being on the reserve, the king scrubs of scrubs, were discovered at the last minute and put into the game to gain the ground and win the game.

A new play devised by Stagg, dubbed the “pile-driving end-back” by the Tribune, helped Perkins bash through the Michigan defense. Short on experienced offensive linemen, Stagg coached his ends to fold in behind the ballcarrier, give him a push downfield, and follow him while “pushing, pulling, dragging, or shoving the man after he was tackled.”

A 28-yard run by left tackle Frederick Fell highlighted an otherwise workmanlike 16-play drive mostly handled by Perkins, who found the end zone from three yards out to bring the Maroons within a point. The score would remain 6-5 after UC failed the conversion.

The teams spent the remainder of the half trading unsuccessful possessions on Chicago’s end of the field. The Wolverines moved the ball as deep as the seven-yard line, only for Stagg’s defense to hold strong.

As the squads regrouped for intermission, the pivotal moment of the day unfolded.

INTRODUCING IPHIGENIA, AKA “PETE”

While the first half transpired, 30 Chicago students wearing “white ducks [pants], broad-rimmed straw hats, and light coats” gathered in the north stands as part of an initiation ritual for the “Three-quarter club.” They were joined by a guest of honor, Iphigenia, whom they called “Pete” for short.

Pete was a rooster.

Holding Pete against his will by a piece of string, the prospective club members made their way towards the field at halftime. I wouldn’t dare change a word of the Tribune’s account for, well, many reasons:

[T]he candidates filed down into the field and gave imitations of a cavalry troop maneuvering, a section of artillery going into action, a Fourth of July parade, a First Ward Democratic caucus, and of Pottawatomie braves on the warpath. Then they sat down to a pow-wow in the center of the field, while the keen wind filled out their duck trousers.

While the tomtoms were sounding and speeches were being made, a blue-shirted Michigan substitute approached warily and mingled with the braves. “Pete” was hopping out to the limits of his tether and was picking corn out of the hands of the candidates when the Michigan man clutched the rooster by the wing, tucked it under his arms like a football, and started for Englewood.

“CHICAGO VICTORY; PERKINS A HERO,” Chicago Tribune, 30 Nov. 1900, archived.

The unnamed “Michigan man” scrambled to leave the scene, unaware that Pete’s tether was stretching ever tighter.