Then-Ohio State head coach Urban Meyer was at the height of his powers in the Spring of 2015. He had just won his third national championship to become only the second coach in college football history to win titles at two different schools.

Most of his championship team returned to Columbus that fall, like Ezekiel Elliott, Joey Bosa, and Mike Thomas. Fans gushed over a potential three-headed monster at quarterback in Braxton Miller, J.T. Barrett, and Cardale Jones.

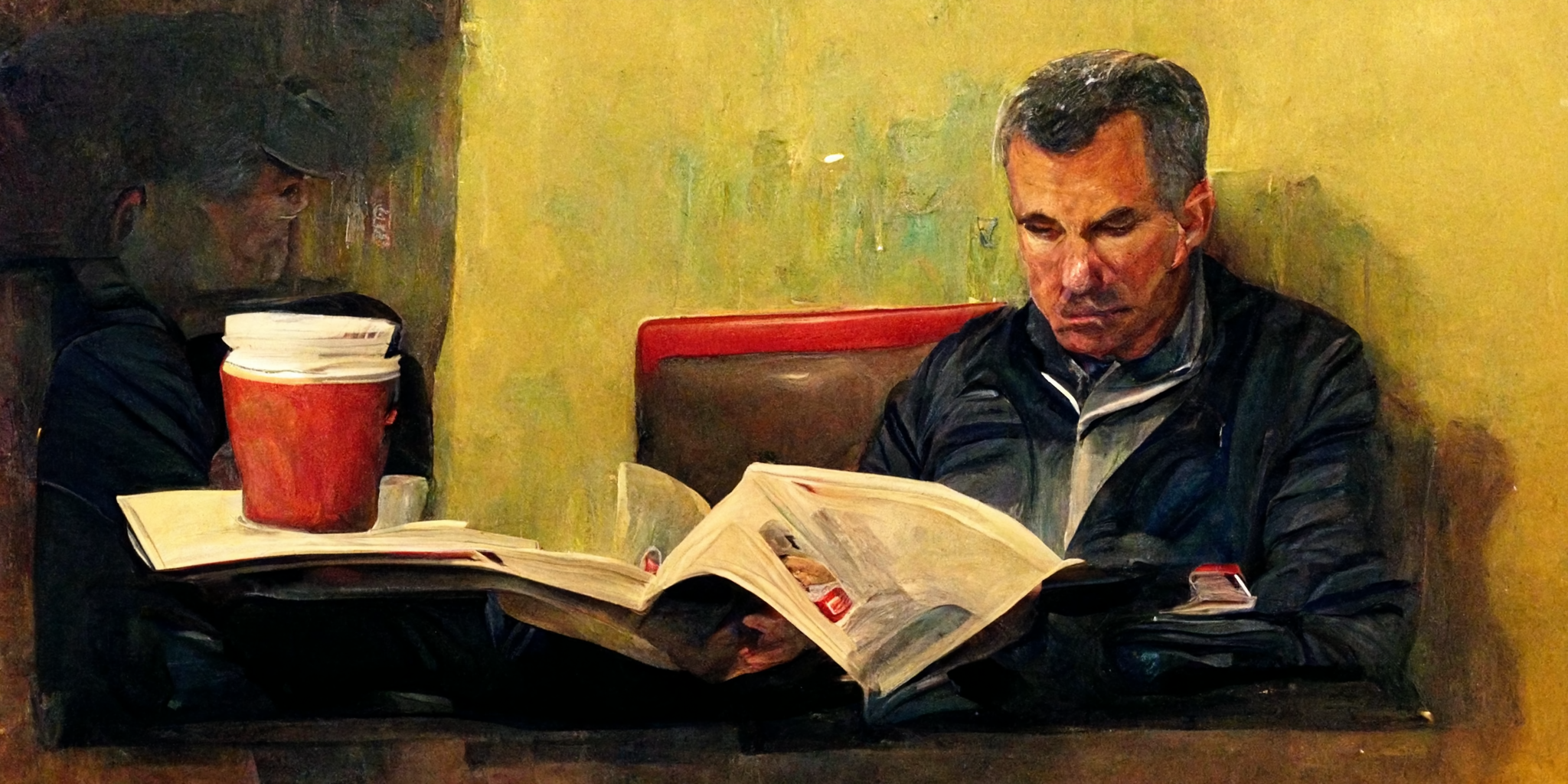

In retrospect, there would never be a better time for Meyer to release a book that would become a national best seller. And that’s exactly what he did with Above the Line, written in concert with sportswriter Wayne Coffey.

In theory, Meyer should have searing insight into the leadership required to marshal a team of 18-22 year-olds into conquering other teams of 18-22 year-olds. And when you’re at Ohio State’s level, the head coach is more of a CEO in charge of a Fortune 500 company.

But even when given the artistic license granted to every memoir, Meyer is still incapable of communicating like he isn’t speaking to a convention room full of middle managers at a corporate retreat in Key West. (One groan-inducing line: “A big part of being a true leader is being open to new ideas. And those ideas come from thinking.”)

The book, when read in 2022, has aged about as well as a used condom on asphalt on a 98-degree day. Readers now have the knowledge of what happened with Meyer in the following six years: Harboring Zach Smith, quitting because Ohio State had the audacity to suspend him three games for harboring Zach Smith, and taking the Jacksonville Jaguars job only to flame-out in the most spectacularly predictable way imaginable.

But you can’t fault a man for not apologizing for sins he has yet to commit. Meyer, however, doesn’t want to discuss any of the sins we know about.

For example, the name “Aaron Hernandez” is not mentioned once. Which, whatever. This was an easy money-grab propelled to the top of The New York Times Best Sellers’ list solely on purchases from business bros reading their annual 25 pages in airports across the country.

Those guys relate to football culture in the same way football coaches relate to military culture.

The tragic thing about Above The Line is you only need to read roughly 25 of the 246 pages to get the gist of the message. The most interesting parts come in the first and last couple of pages. The rest is a level of writing usually reserved for Entourage episodes.

My first highlighted passage comes at the top of Page 2.

“A leader is not someone who declares what he wants and then gets angry when he doesn’t get it.”

I’ll give Urban this much: He made me aware early that he thought publishing this book would capstone his emotional journey from overbearing megalomaniac to a serene teacher of zen. He was blissfully unaware that would be a journey for the rest of his life.

That’s how, as coach of the Jacksonville Jaguars, he kicked his kicker in the one muscle he needed to help the team before a preseason game. He is physically incapable of taking his own advice. But I digress.

One of the two most insightful passages begins at the bottom of Page 2 when Urban remembers a time he ran eight miles home as a senior in high school after a rivalry game ended with him striking out by refusing to swing at a belt-high fastball.

Some of the people had the idea that my father, Bud Meyer, a tough guy who was old school even by old school standards, ordered me to run home as punishment for coming up small. My father was not beyond doing that.

Some of the people got that idea from an article by Pete Thamel of nytimes.com in 2007, the day before Ohio State faced Meyer’s Florida in the BCS championship—an interview in which Meyer himself participated.

PARADISE VALLEY, Ariz., Jan. 6 — Dean Hood remembered making plans to hang out with Urban Meyer after a baseball game during their senior year of high school. Meyer had three hits and made a diving stop before making the last out in a loss. Hood recalled vividly that Meyer was the best player on the field that day, but not good enough for his father, Bud.

“I can’t leave with you,” he recalled Meyer saying to him. “My dad’s making me run home.”

“I couldn’t tell you how far it was, but it was a long way, man,” said Hood, who is now the defensive coordinator at Wake Forest.

Meyer could have left it there. But he continues into the bizarre:

“One time when I was in third grade and getting into some mischief in Mrs. Stofko’s class, she asked my dad how he wanted her to handle it.

‘Paddle him. Use a ruler. Punish him any way you want,’ my father said.”

Making your kid run eight miles after losing a game in which he played well and turning him over to the Catholic church for corporal punishment are the actions of a guy who has no problem slapping his own child around at home.

It doesn’t stop there.

Meyer continues with a tale from third grade. A first-grade boy “wouldn’t leave [his sister] alone.” Bud told Urban that he “needed to take care of it.” So, the next day, Urban, “as directed by [his] father, … punched him in the face… It was the first punch [he’d] ever thrown.”

The punch sent him to the principal’s office, but his dad “treated him like a hero,” even taking the family out to dinner and allowing young Urbs to sit at the head of the table. “You’re a man now. Family is everything.”

When you add in the fact that Bud Meyer donated $4,000 in 1980 ($14,382 in 2022) to Holocaust-denying presidential candidate Lyndon LaRouche, it becomes clear that Meyer got beaten as a child and his paranoia didn’t fall far from the tree.

”One night I fell out of bed and sprawled facedown on the floor, my chest feeling as it were being crushed by an anvil as Shelley, a trained nurse, spoke to a 9-11 operator. My friend […] had died of a heart attack at age fifty-two just a few years ago.

”Was I going to be next?”

– Urban Meyer

Page 17 of above the Line

On Page 18, before embarking on a trip to Israel in 2010, Meyer subjected his family to a showing of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ. The date is notable because it came decades after Gibson had been exposed as one of Hollywood’s leading anti-Semites.

He came back from that trip once again thinking he had been forever changed.

“I cringe when I look back at how I was at age thirty-six when I got my first head coaching job at Bowling Green. I was a raving lunatic a lot of the time. It might have changed a bit at Utah and Florida, but not by much. These days I am much more purposeful and intentional.”

Again, hilarious stuff knowing what we know about Urban’s trajectory since publishing Above the Line.

It does serve as the perfect segue into the introduction of Tim Kight, Urban’s leadership guru who claims to have ran track at UCLA despite there being no record of a Tim Kight running track at UCLA:

“In the old days, Urban got furious. Now he gets curious.”

[…]

“The amount of training that he has done with his team—coaches and players—is unprecedented. Probably more than any team college football history. He is constantly filling their tool box.”

We never did find out how much money Kight made off his leadership consulting with Ohio State. But hey, he had phrases that rhymed and an ability to laud the man who signed his paychecks, so it was probably an investment worth every penny.

Most of Urban’s leadership advice comes from the “Event + Reaction = Outcome” system that any Ohio State fan worth their weight in salt is familiar with.

The system would look better in retrospect if time ended right after Meyer lifted the 2014 CFP trophy. Instead it looks like over-simplified, self-aggrandizing hogwash considering what we know about the circumstances of how Meyer left Columbus and Jacksonville.

Meyer starts chapter four, “The Foundation,” with this paragraph:

“Let’s get something straight before we go any further. Ohio State won the 2014 national championship because we have great players who played great. The coaching staff can make a significant impact, but the athletes are the ones who make the plays. It bothers me when I hear so-called experts going on and on about coaching brilliance and how somebody’s schemes are so much better than everybody else’s.

“That’s nonsense.”

I want to thank Urban for writing such a succinct summary of why players deserve not only Name, Image, and Likeness rights but also to be classified and protected as employees. This is as close as you will ever come to see Meyer reckoning with how he earned a majority of his wealth on the backs of exploited, predominantly Black athletes.

But, like many reactionaries, Urban arrives on the doorstep of a revelatory point yet refuses to step through the threshold of the building.

Does Urban support any of that stuff? Hell no.

He wouldn’t even let his players wear hoods in the training facility. He stood in the way of every modicum of player rights because he only knows how to coach in the state of a tinpot dictator.

It’s a lesson he learned from his mentor, Earle Bruce.

Meyer’s paranoia is legendary in coaching circles, and we get a glimpse into why on Page 150 in a chapter entitled, “The Necessity of Alignment.”

Meyer details a time at Colorado State where “things were going great until a couple of coaches on Coach Bruce’s staff began to undermine him, running to the athletic director, spreading rumors about the program being out of control. It was nasty.”

Meyer, to his credit, doesn’t pretend to be a neutral observer, but he laments all these years later that he did nothing to stop their “betrayal” of his mentor.

Meyer never explains what exactly he means by “alignment” which means he is talking about all of his assistants doing what he wants at all times. This is a point he labors to every underling and their wives every preseason for some reason.

“I’m so committed to never going through anything like that again all these years later, I have a conversation with my coaches and their spouses before every season, and let them know that to me disloyalty is insubordination, and if you are insubordinate you are gone. It’s not, ‘Oops, sorry. I didn’t mean anything by it.’ It’s ‘Pack your bags and get out of here.’”

I don’t care how much money you pay me or how prestigious my job is. The only way I am taking my wife to a performance review with my overbearing boss is if she is my overbearing boss.

Hard to believe that Meyer consistently burned through the talented assistants he hired at every stop and why he could only replace them with yes-men he “trusted” in the long run.

Most of Urban’s recollections on games consist of a blow-by-blow accounting of the famous games we all watched en route to the championship. It makes for dull, predictable reading with lines like, “It was two elite warriors making an elite play.”

However, the second most insightful part of the book comes on Page 229, in the chapter entitled “The Chase is Complete,” when Meyer cops to showing his team a snuff film before the championship game against Oregon.

“My message to the team was about how for the past year, our clarity of purpose was not to make it to the national championship, but about getting to Nine Units Strong. If we finish this game Nine Units Strong, we’ll be champions of college football.

“As I closed my message to the team, I said, ‘You’re about to see a clip at the end of the video about the unit who took out Osama bin Laden. They are the best of the best in the military. They are elite. They were given a mission, and they accomplished that mission.

“At the end of the clip, after they killed him, one of the guys looks at the shooter and asked, ‘Do you even realize what you just did?’ and you can see what just happened.

“Tonight, when the clock strikes zero, you’re going to look around at your guys, at your unit, and you’re going to ask, ‘Do you even realize what you just did?’

“I paused for a moment.

“You’ll be able to look right back at him and say, ‘We’re national champions.’”

This is why Meyer is him, and we aren’t. None of us would ever think to motivate a college football team by showing them a video of a unilateral, extrajudicial assassination on foreign land.

I can’t argue with the results since Ohio State entombed Oregon at the bottom of the sea, much like the United States did to Osama bin Laden.

TL;DR: Meyer should have immediately retired after publishing this book that instantly became a New York Times bestseller. He had nothing left to prove in his profession, and he could’ve made buckets of money by speaking at company junkets around the country, pitching his voodoo leadership system.

Unfortunately, the man is a special breed of pervert. He can’t stay away from the scent of victory because after all these years, he’s still trying to prove his worth to his long-deceased father.

Buckeye Nation can thank Bud for not hugging his son because that 2014 title doesn’t happen otherwise.

As for the rest of the book, it was droll even before Meyer cemented himself as a massive hypocrite who hasn’t changed throughout his career.