This article is free to read. Please consider subscribing to Meet at Midfield for more analysis and content like this article, exploring both national college football, the entire B1G, and Ohio State.

As of mid-May, with nearly all of the hay in the barn, Ohio State is rolling into the 2024 college football season with just 82 scholarship players on the roster of the maximum 85.

With the advent of NIL collectives covering scholarship and other attendance costs for scholarship players over the limit, we’ve seen programs like Oregon, Michigan, and Nebraska push the boundaries of whether that 85 is even a real limit anymore. Yet still, Ohio State sits well below the limit and is likely in a position where it will be elevating mostly unproven walk-ons – T.C. Caffey, Inky Jones, Patrick Gurd, et al – on the third string of the depth chart to scholarship positions.

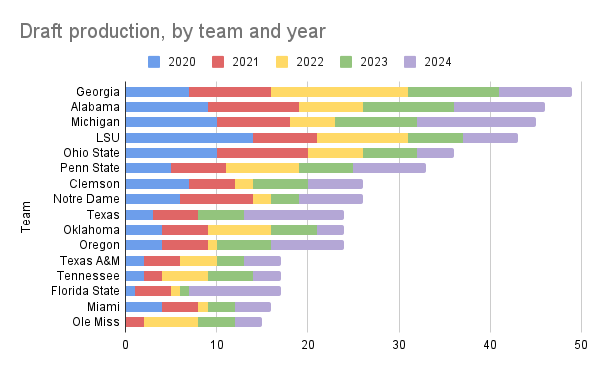

All of this comes as the Buckeyes have lost three straight games to Michigan for the first time in nearly 30 years; as they’ve produced their lowest five-year cumulative total of drafted players since before Urban Meyer’s first recruiting class became draft eligible; and as player acquisition and processing becomes easier than ever with the rise of the transfer portal, NIL collectives, and functionally flexible scholarship limits.

Despite being one of the most effective programs in recruiting in terms of average player ranking and perhaps the single richest program in college football, easily able to take full advantage of NIL, the Buckeyes have simply been cautious in player acquisition. They’ve added fewer players over the last five years – 2020 to 2024 – than nearly any other nationally relevant program.

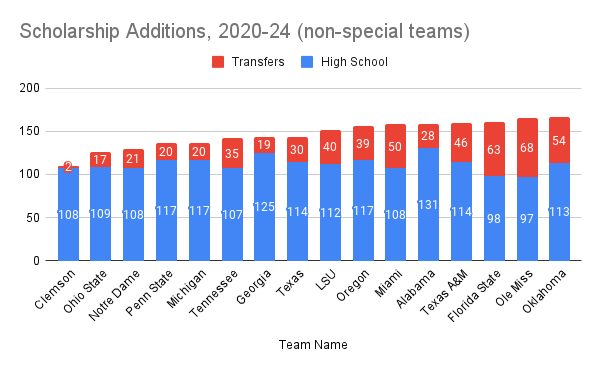

I compared the Buckeyes to 15 other national programs who have had some mixture of on-field and recruiting success – Georgia, Alabama, Michigan, Penn State, Oregon, Texas, LSU, Clemson, Notre Dame, Texas A&M, Oklahoma, Florida State, Miami, Tennessee, and Ole Miss – as well as the entire B1G conference, including new additions for the 2024 season.

Ohio State ranked nearly dead last in total non-special teams additions of scholarship players, adding 126 players to the program in the five-year range we’re examining. Only Clemson trails the Buckeyes and Notre Dame is the only other program even in the same ballpark.

The difference largely comes from the lack of portal additions. Ryan Day’s Ohio State is in the middle of the pack in high school signings over that time period. They rank 10th, but schools ranked no. 3 through no. 14 are only separated by an average of two high school signings per year.

Clemson’s retrograde program is by far last in transfers, adding just two players (one of them a player they signed out of high school who left and then came back home) in five years. Ohio State is next-to-last after the Tigers, but in the same range as Michigan, Penn State, Georgia, and Notre Dame. There is a negligible difference overall between the Buckeyes and Irish, but each of those first three programs signed nearly a dozen or more total players than Ohio State over that window.

That may sound like a small number, but those marginal gains to roster talent and the ability to cycle through the lowest-performing or least-promising players on the roster is a huge boost to depth and future roster performance. When you’re competing at this nationally competitive level, the small margins are what determines the difference between winning national championships, as Georgia and Michigan have done, and missing the playoff entirely, as Ohio State did twice in the last three seasons.

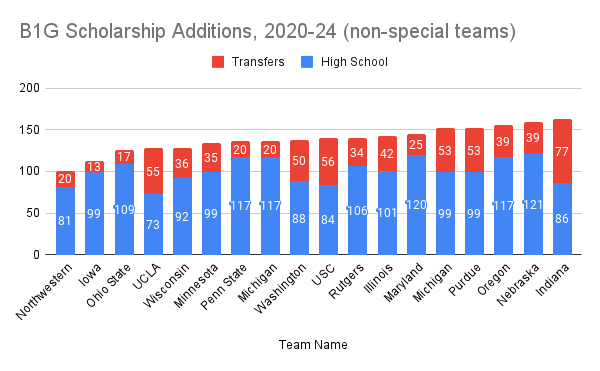

Some may choose to point to cultural and procedural differences in the Big Ten, where teams are less likely to push the (unofficial) boundaries in oversigning or processing on rosters. However, the story is much the same within the league. Ohio State ranks 16th among the 18 teams in the new B1G in additions over a five-year period. Iowa, with its 1998 roster-building mentality, and Northwestern, which has the same problem compounded by strict academic requirements, are the only programs trailing Ohio State.

The simplest culprit to point to is, as mentioned above, the lack of transfer additions compared to most programs. We know Ohio State is in the middle-of-the-pack on high school signings, but towards the very lowest end of normal on transfer additions. However, it’s easy to make a compelling argument that the Buckeyes are also not signing enough high school players.

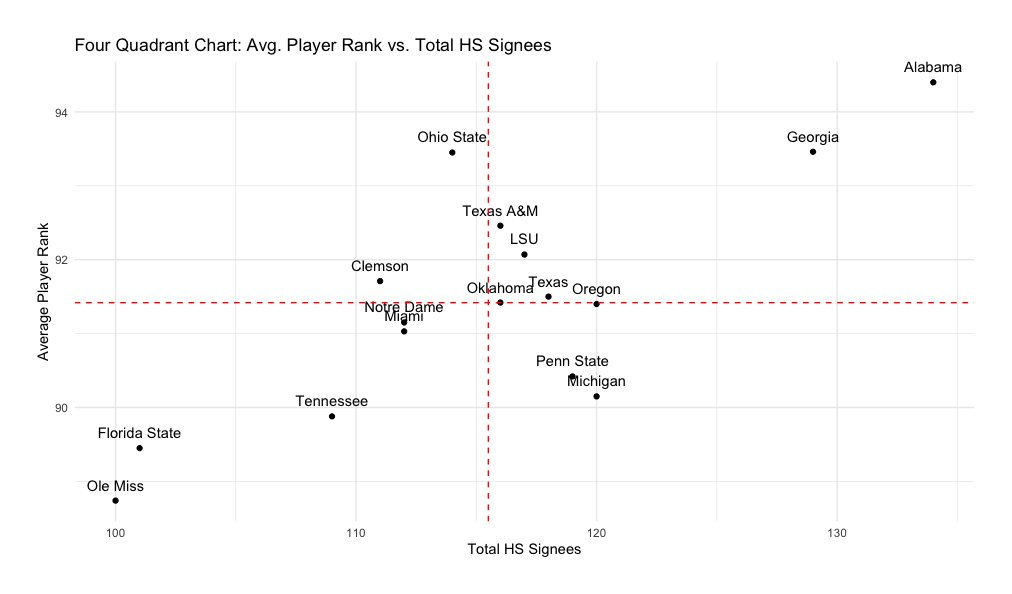

While they may be in the middle of the pack on those high school signings in terms of total numbers, Ohio State is in the very highest reaches of average player ranking among high school prospects. The Buckeyes are in very rare air when it comes to the quality of player they sign. A 93.45 average player ranking over five years trails only Georgia (barely, with a 93.46 average) and Alabama (94.40).

Yet Ohio State signs significantly fewer players than either of those programs – 15 fewer than Georgia and 20 fewer than Alabama over that period of time. When you compound those numbers with how much they trail each in transfer additions (two fewer than Georgia, 11 fewer than Alabama), the Buckeyes’ strategy essentially cedes an entire extra class of players to the two other elite recruiting programs over a five-year period. That matters a ton.

If you want to point towards a culprit for why they sign fewer players, there are different discussions to be had. There are certainly anecdotal points to situations where Ohio State has zeroed in on a small handful of top targets and not appropriately prepared backup plans — think defensive line or running back recruiting in the last two or three cycles — but if you want to start at the baseline, Ohio State simply offers few players than most top teams. It is too stingy with who they recruit in the first place, in comparison to their peers.

The Buckeyes offered four to five hundred prospects than Alabama or Georgia over a five-year period. They offered less than half as many as Michigan. They’re simply not very active on the trail when it comes to evaluating and offering new targets and are way down in that regard post-pandemic. Here’s a visualization of those scholarship offers, per year, by school:

And to bring it back to the comparison with the SEC’s top two programs, it’s not like Alabama or Georgia have experienced massively more attrition than Ohio State has. If you discount the fallout from Nick Saban’s departure, Alabama was on track to have 66 transfers out of the program in the five-year period, barely more than Georgia’s 63. Very few of those players have gone on to be difference makers elsewhere too. Drew Sanders and Javon Baker were the only real losses for the Tide. And it’s just Clay Webb, Jermaine Burton, AD Mitchell, and Bear Alexander for Georgia.

Ohio State’s story isn’t much different from those two. Quinn Ewers, Javontae Jean-Baptiste, and Jameson Williams went on to be productive players elsewhere, but that’s still a short list.

The lesson we can learn from that is that the Buckeyes must be churning through the non-performers on their roster faster and bringing in equivalent or better talent to replace them. Even if you lose an eventually productive player every year or two, you’re very likely to replace them easily with the level of talent being brought in and will almost never lose a productive starter to the portal that you wanted to keep.

As mentioned above, this has led to Ohio State’s worst five-year cumulative draft production since 2013-17. That stretch was a result of the middling end-of-term recruiting from Tressel and the two transition classes between Tressel, Fickell, and Meyer. Despite recruiting the third-best player average in the country, the Buckeyes have not yielded similar fruit in draft production. They fell to fifth in the country in the 2020-24 range in total draft picks.

You could certainly point, as I have many times, to the missteps in strength and conditioning and staff management under late-stage Urban Meyer and Ryan Day’s first five seasons, but the Buckeyes are still putting top five or ten-ranked teams on the field most years. The disconnect between that on-the-field production and results in both the most important games and the NFL Draft are certainly at least partially due to Ohio State refusing to maximize its roster with all of the talent available to them.

Letting dead weight sit on the bottom of the roster for four years and not aggressively oversigning in an era where you can expect approximately a third of the roster to churn out every year is malpractice.

Trey Leroux spent four full years on Ohio State’s roster to play 16 total snaps. His classmate, Grant Toutant, was on the team for the same length of time with zero snaps. Kamryn Babb averaged 25 snaps per game over the course of five years. Kourt Williams hasn’t played in a game since week six of 2022, but is still on the roster. Zen Michalski played just 21 offensive snaps last year with no injuries and is entering his fourth year on the team. Tyler Friday played 72 total defensive snaps in his fourth and five years with the team.

You don’t need four or five years to determine if a player is capable of contributing anymore. This is not the 1990s where you expect a player to redshirt, ride the bench in his second year, and maybe contribute in year three if he’s excellent. Rosters churn faster than that and players seek playing time as early as possible. A passive approach to roster management allows detritus to hang out on the bottom of the roster without a plan for deliberate replacement, meaning you only lose the middle of your roster or talented young players blocked by middling depth.

The idea of football as an amateur sport with loyalty between players and coaches being built over four or five years has been dead for at least a couple decades, but the truth of the current circumstance has been exposed more than ever with the transfer portal era. Both players and coaches are self-interested to find the best opportunities to show their talents as quickly as possible. Rejecting that reality by being cautious in the transfer portal and signing small recruiting classes consistently simply cannot continue to happen.

If Ohio State continues to add approximately four scholarship players per year fewer than Georgia and seven fewer than Alabama, it will continue to fall short of those national powerhouses, even with Nick Saban gone. Even Michigan, with its pearl-clutching over “building teams the right way” and its fan base’s obsessions with allegedly more difficult academic requirements, has signed 2.5 more players per year than Ohio State.

Those departures of coaching legends like Saban and Jim Harbaugh, Dabo Swinney deliberately taking his program out of the title race for personal objections over the state of the sport, the expansion to a 12-team playoff, the full weaponization of the massive Ohio State fan base into one of the country’s best NIL operations, and most other things occurring in the sport right now have busted the title window wide open for the Buckeyes. If they want to keep it that way, they need to recruit and manage their roster like a modern college football team and understand the realities in front of them.

Fans and journalists alike have praised Day for being “aggressive” in the transfer portal despite taking just six new scholarship players. Time will tell if those additions – that ignored the offensive line issues and didn’t upgrade on middling linebackers and tight ends or add experience to a young wide receiver room – combined with excellent roster retention for 2024 are enough to get over the hill for a championship this year. But continuing to act more like Clemson or Iowa than Georgia or Alabama when it comes to roster management means that Ohio State won’t be taking full advantage of the opportunities in front of them in years to come.

Ohio State pays Ryan Day more than ten million greenbacks per year. Its staff salary expenditures were the highest in the country last year and just increased significantly. It spends as much on NIL as any team in America, maybe sans Oregon. It is beyond capable of figuring these challenges out and it is on Day’s shoulders to do so. The path forward is clear, should he choose to take it.