The stakes are as high as they get.

Michigan prepares for a winner-take-all game in Columbus. Led by an All-American player-turned-coach, the Wolverines and their fans carry more optimism into The Game than they have in years. Ohio State has previously seemed unbeatable under their highly regarded coach but the momentum has shifted north over the past year.

It’s 1964.

The Coaches

After serving as a lieutenant in the Marines at the end of World War II, Chalmers “Bump” Elliott starred at halfback in Michigan’s famed “Mad Magicians” backfield alongside his brother, quarterback Pete Elliott. Despite playing only two seasons in Ann Arbor because of a pre-war tenure at Purdue, Bump left an indelible mark.

Elliott’s two-way exploits helped propel U-M to the 1947 national championship. He led the ’47 team in scoring, finding the end zone as a rusher, receiver, punt returner and defender. He was the second Wolverine since 1943 to record a 100-yard receiving game and the first to do it twice. To this day, he’s fifth in career interception return yards with 174.

The Western Conference controversially denied Elliott a wartime-related extra year of eligibility for 1948, a choice Michigan Daily sports editor Dick Kraus wrote was intended “to hamstring the champions” in his recurring column Just Kibitzing. Bump joined the coaching staff for a year, spent a decade as an assistant at Oregon State and Iowa, returned to Ann Arbor under fellow legend Bennie Oosterbaan in 1957 and ascended to the head job for the ’59 season.

Wayne Woodrow Hayes requires little introduction. He arrived in Columbus from Miami (OH) in 1951. By 1964, he’d won four Big Ten titles and claimed three national championships. The more colorful pages of his lore had yet to be written.

Meanwhile, Elliott struggled to get Michigan on level footing. Oosterbaan went 2-6-1 in his final season. From 1959-63, Elliott’s teams went 20-23-2 overall and never placed higher than a tie for fifth in the Western Conference. U-M had lost four straight to Ohio State after beating an uncharacteristically bad Buckeyes squad in Elliott’s debut season, tying their worst skid in rivalry history (1934-37).

The Buildup

In 1964, Hayes’ Buckeyes spent eight weeks in the AP top five, including two at No. 1, before a shocking 27-0 home loss to unranked Penn State knocked them down to No. 7 entering The Game. Since PSU was still decades from joining a conference, however, OSU sat atop the West heading into the final week of the regular season.

Three Buckeyes would be named 1964 All-Americans: defensive back Arnold Chonko, left tackle Jim Davidson and linebacker Ike Kelley. Two more future All-Americans, guard Doug Van Horn and center Ray Pryor, anchored the offensive line with Davidson. Chonko and Kelley later made OSU’s All-Century team.

For the first time since the mid-50s, Michigan remained in the conference title race to the end, only a 21-20 defeat against third-place Purdue away from a perfect record. Star QB Bob Griese’s Boilermakers had since lost two conference games, so the winner of Michigan-OSU would go to the Rose Bowl.

The Wolverines had a pair of soon-to-be All-American of their own: quarterback Bob Timberlake and defensive lineman Bill Yearby. Sixteen players from the 1964 team went on to play in the NFL or CFL, not including star halfback Jim Detwiler, who never played a down after getting drafted in the first round by the Baltimore Colts because of a knee injury.

The Detroit Free Press reported a new-found feeling in Ann Arbor: optimism.

They talked of Michigan-Ohio State football games—which is normal enough since those old enemies play this week—but there was a difference.

There wasn’t that worrisome air that preceded defeats at the hands of the Buckeyes for the last four autumns.

At moments, the conversation almost had a ring of confidence in the face of an impending Saturday visit to Columbus.

They were even questioning Bump Elliott about whether he would go for one-point or two-point conversions after touchdowns.

Even though Michigan hadn’t won in Columbus since 1956, Elliott gave a straight answer to the conversion question: if U-M felt confident they’d score again, they’d “probably” kick the one-point conversion.

The Game

Not only is Michigan-OSU the greatest rivalry in sports, it may be the best-documented. If you’re so inclined, you can watch this entire game:

Although both offenses were well-regarded, the vaunted defenses controlled the cold, wind-swept game from the outset. This was the most stressful type of rivalry game: one resting on the knife’s-edge of turnovers and scant few scoring opportunities.

The first six drives ended in punts as neither squad could advance closer than 38 yards from the opposing end zone. Michigan blinked first. Timberlake was stripped from behind trying to convert a third-and-two and OSU end Thomas Kiehfuss recovered at the U-M 29-yard line.

Ohio State failed to take advantage. The offense moved the ball only two yards to set up a 44-yard field goal attempt. Robert Funk’s kick landed so short it played to OSU’s advantage; they downed the miss at the one, which was allowed in the rules at the time. (The ball also bounced back into the field from the end zone, the rules have evolved quite a bit.)

Michigan burrowed their way to the six before punting back to the Buckeyes; the boot only went to the U-M 33. After going nowhere in three plays, Hayes took a gamble, faking a long field goal. The holder, Chonko, completed his pass to Thomas Barrington, but the Wolverines rallied to stop him short of the first down.

As the half neared a close, Michigan finally got a momentum swing in their favor. Naturally, it came on a punt. Robert Rein couldn’t handle a high, hanging boot from Stan Kemp; U-M’s John Henderson pounced on the loose ball at the OSU 20.

At a strapping 215 pounds, Timberlake was “a fullback slamming for vital short yardage rather than a quarterback trying light-footed sneaks,” as the Free Press later described him.

“He’s so big and strong,” said Alex Agase, coach of the Northwestern team hammered, 35-0. “You can have him trapped for a loss and he’ll get away for a 30 or 40-yard gain.”

Timberlake’s best play wasn’t a long one. On the original box score, the play-by-play account on U-M’s ensuing first down reads “Timber wide left for 3.” That doesn’t quite capture Timberlake’s weaving field reversal to salvage a broken play.

On the next snap, Timberlake dropped back to pass with a half-roll to the right, looked back to the left and connected with halfback Jim Detwiler on an angle route. Detwiler pulled the ball down in traffic and dove through a desperation tackle for a 17-yard touchdown with only 44 seconds on the clock.

Evidently confident his squad could do it again, Elliott called for a one-point conversion, which reserve quarterback Forest Evashevski Jr. kicked true for a 7-0 lead. Evashevski, son of the former U-M player and legendary Iowa head coach and athletic director, was better known by the nickname “Frosty.”

In 1965, Woody Hayes had to be restrained from fighting the senior Evashevski at a meeting of conference coaches. That’s another story for another time. Neither man was the type to avoid confrontation.

Returning to 1964, the teams were statistically level at halftime, with the only difference being that U-M finished a drive. The Wolverines had mustered 87 yards on 27 plays, the Buckeyes 85 on 28. Aside from the final Michigan drive of the half, every possession ended in a punt, lost fumble or turnover on downs.

The third quarter didn’t break that trend. Let’s breeze through the period with a quick drive summary:

- Ohio State punt

- Michigan punt

- Ohio State punt muffed by Michigan, recovered by OSU near midfield

- Ohio State lost fumble two plays leter

- Michigan missed field goal

- Ohio State punt

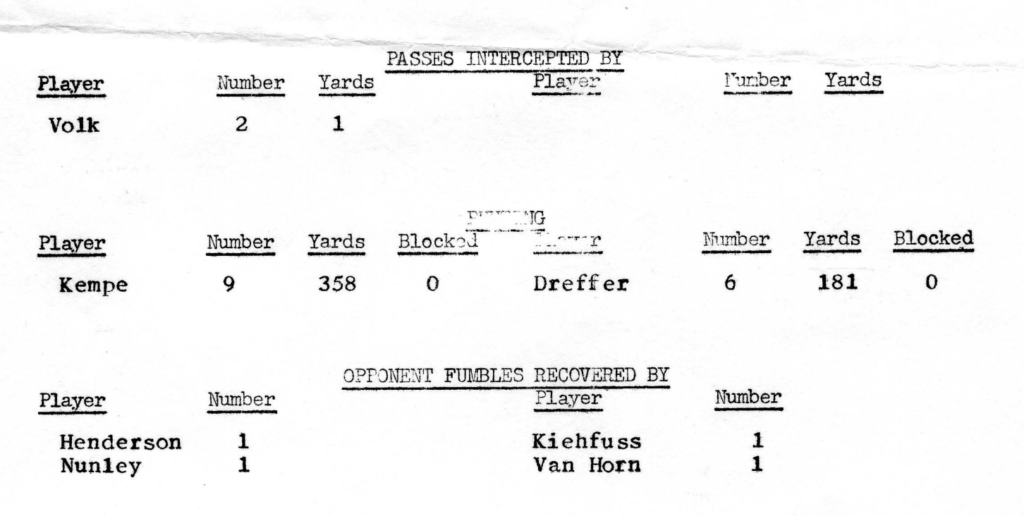

Michigan’s second big break came on that final OSU punt of the quarter, which Rich Volk fielded just inside U-M territory before breaking through a couple tackles and spinning down to the OSU 24.

Fullback Mel Anthony rumbled up the gut for 12 yards on first down. Although U-M’s offense stalled as the game entered the fourth quarter, they were plenty close for Timberlake to knock a field goal through the uprights.

The players, coaches and Maize and Blue faithful who’d traveled to Columbus could smell U-M’s first Rose Bowl since 1950. They could no longer maintain their composure.

Up until Timberlake’s field goal in the fourth period, cautious enthusiasm had been the rule among the fans, spread throughout the east side of the horseshoe-shaped stadium. Quite suddenly it bloomed into unrestrained joy as Michigan students realized that they would be spending Christmas vacation in Pasadena.

Even with three minutes remaining in the game, band members could be seen pounding each other on the back, and fans lined the ropes and shouted encouragement at the players. One man yelled “God love you Jim Conley … God love you Bill Yearby …” at each player he saw. With less than a minute to go, “Rose fever” spread to the players and even coaches could be seen jumping up and down.

Volk ensured the Buckeyes couldn’t come back from a 10-0 deficit. With OSU set up in scoring territory after a couple chunk runs, primed for an immediate answer to Timberlake’s field goal, Volk snared an ill-advised scrambling toss by Buckeyes QB Donald Unverferth.

After the teams traded failed drives, Volk repeated the feat, this time getting airborne to intercept a long pass down the sideline.

He broke up a fourth-down pass to finish off OSU’s next, and final, turn with the ball. Timberlake ran out the final seconds. Michigan fans streamed onto the field to celebrate.

Approximately 3,000 delirious Wolverine rooters broke through a rope held by fuming Columbus policemen and pounded their heroes backs for ten minutes Saturday before the ‘Victors’ were escorted to the comparative quiet of the locker room.

The Michigan supporters had journeyed on icy highways and sat through numbing cold for three hours but, as one fan put it, “One day of freezeing is nothing compared to 14 years of waiting…” Another stood with tears of joy in his eyes and stammered, “I can’t believe it. I can’t believe it.”

Elliott called the game “the greatest thrill” he’d ever had. In the other locker room, Hayes lamented “they took advantage of their breaks and we couldn’t make the most of ours.”

Ohio State outgained Michigan, 180 total yards to 168, and attained 10 first downs to U-M’s nine. The Buckeyes were penalized less, punted less and averaged more kick return yardage. They recovered two of three U-M fumbles, while the Wolverines grabbed two of OSU’s six.

But Timberlake, despite completing only three of nine pass attempts, finished with zero interceptions. Kemp, meanwhile, outkicked his Buckeye counterpart Stephan Dreffer by nearly ten yards per punt. Bump’s boys prevailed not only by big plays but also gaining a slight advantage around the margins.

The Aftermath

1964 would be Elliott’s finest season as Michigan’s head coach. They finished 9-1 and ranked fourth in both major polls after a 34-7 romp over Oregon State in the Rose Bowl. They were a game-ending two-point conversion against Purdue away from a perfect season and national championship. Regardless, powerhouse Michigan was back.

Or so it seemed.

Bump’s next three teams went 4-6, 6-4 and 4-6, respectively, and their only win out of three against OSU came against Hayes’ 4-5 1966 team. Michigan won eight of their first nine games in 1968 only to be humiliated in the infamous “because we couldn’t go for three” 50-14 loss at Ohio Stadium.

Amid ultimately unsubstantiated rumors that new athletic director Don Canham had issued an ultimatum to beat Ohio State or be fired, Elliott resigned after the game. Canham replaced him with a former Hayes assistant who’d gone 40-17-3 as the head coach at Woody’s old stomping grounds of Miami (OH): Bo Schembechler.

Thus ensued the Ten-Year War.